Art Basel Miami 2023

Invasive Species

2023 Installation view Art Basel Miami

Invasive Species

2023 Installation view Art Basel Miami

Invasive Species

2023 Installation view Art Basel Miami

Invasive Species

2023 Installation view Art Basel Miami

Invasive Species

2023 Installation view Art Basel Miami

Invasive Species

2023 Installation view Art Basel Miami

Invasive Species

2023 Installation view Art Basel Miami

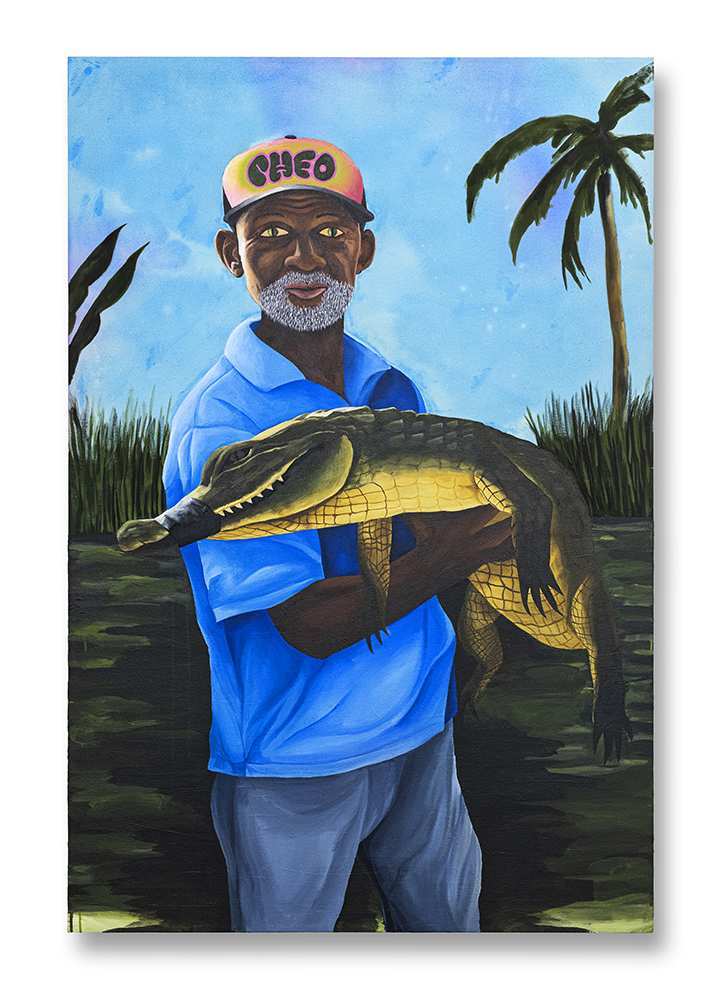

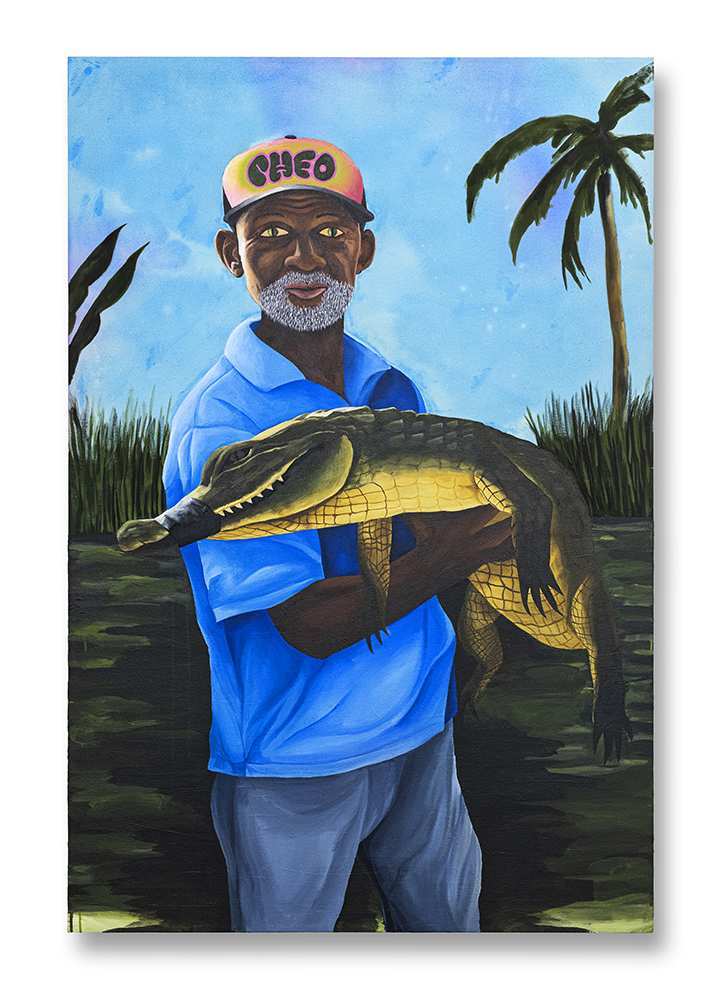

Don Cheo, Ojos de Caimán

2023 Acrylic on canvas 60 x 40 in

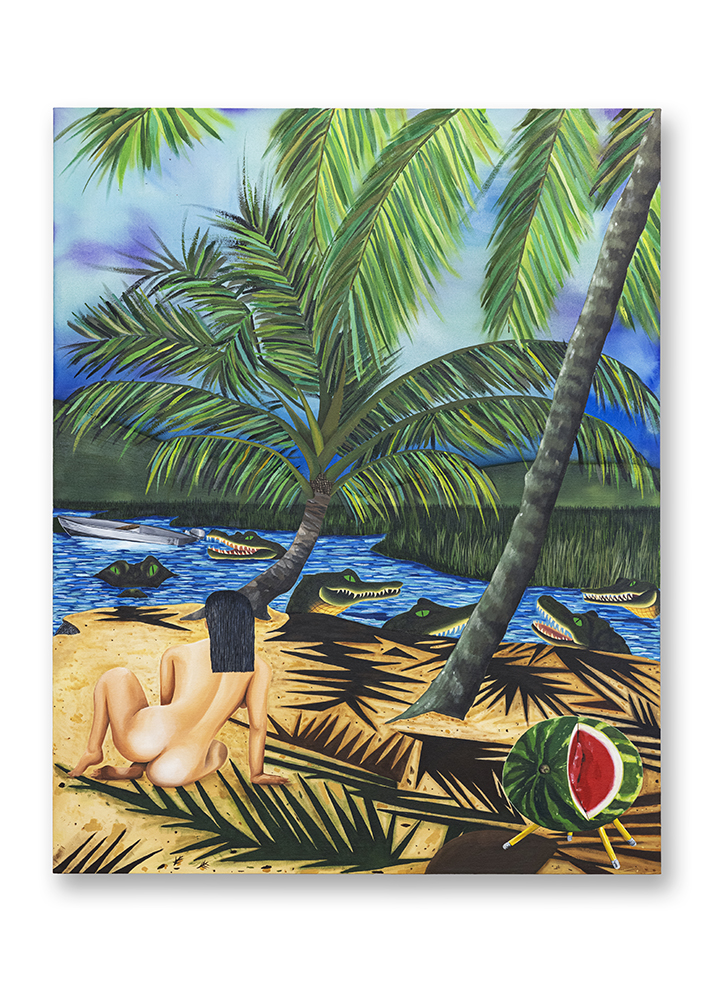

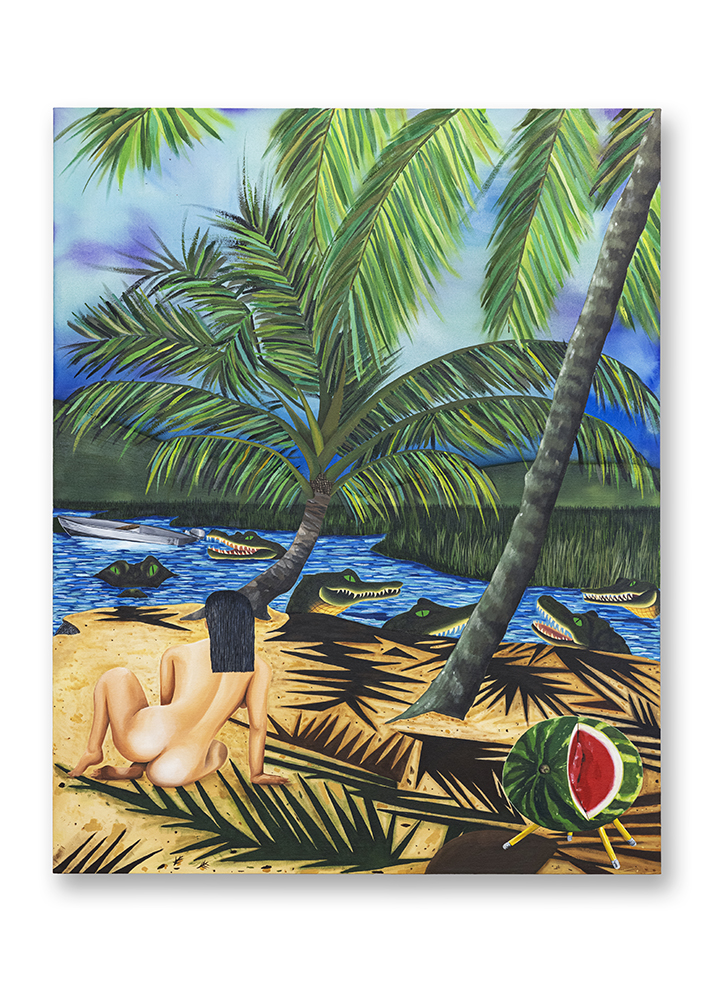

Looking for the Watermelon (Playa Los Bohios, Maunabo)

2023 Acrylic on canvas 60 x 48 in

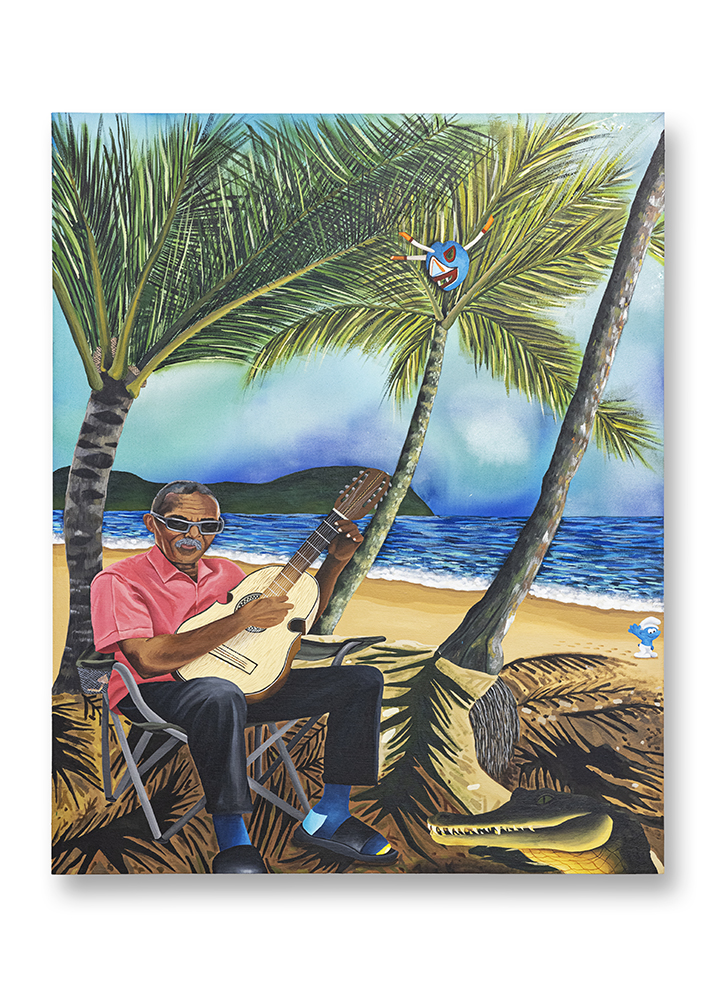

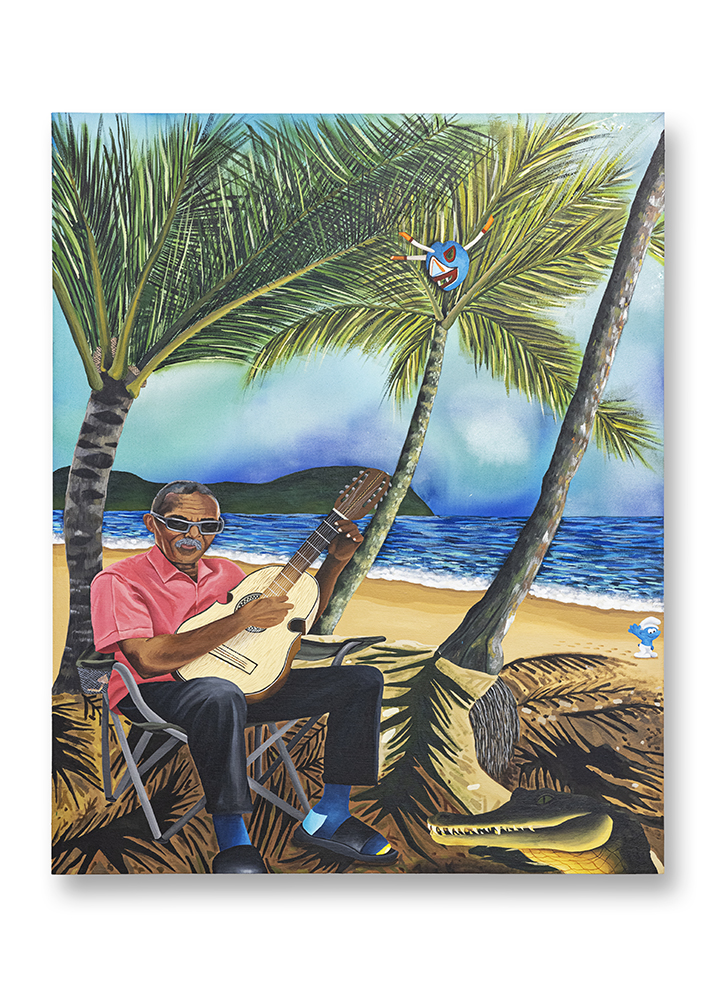

Psychedelic Afternoon Under a Palm (Playa Los Bohios, Maunabo)

2023 Acrylic on canvas 60 x 48 in

Night Fishing in Canovanas

2023 Acrylic on canvas 53 x 84 in

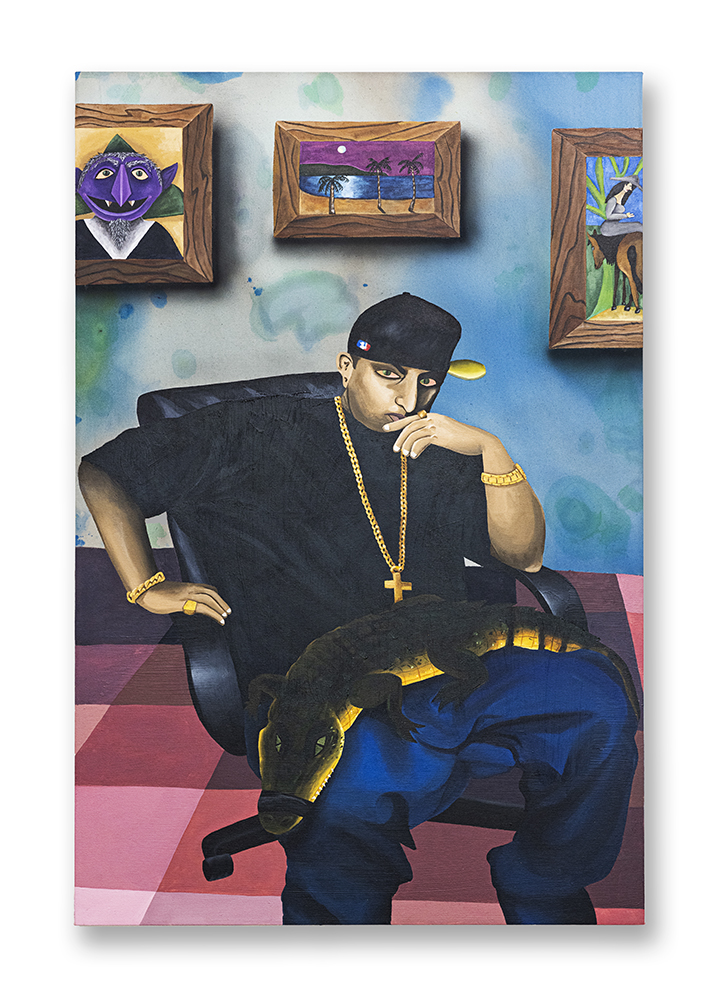

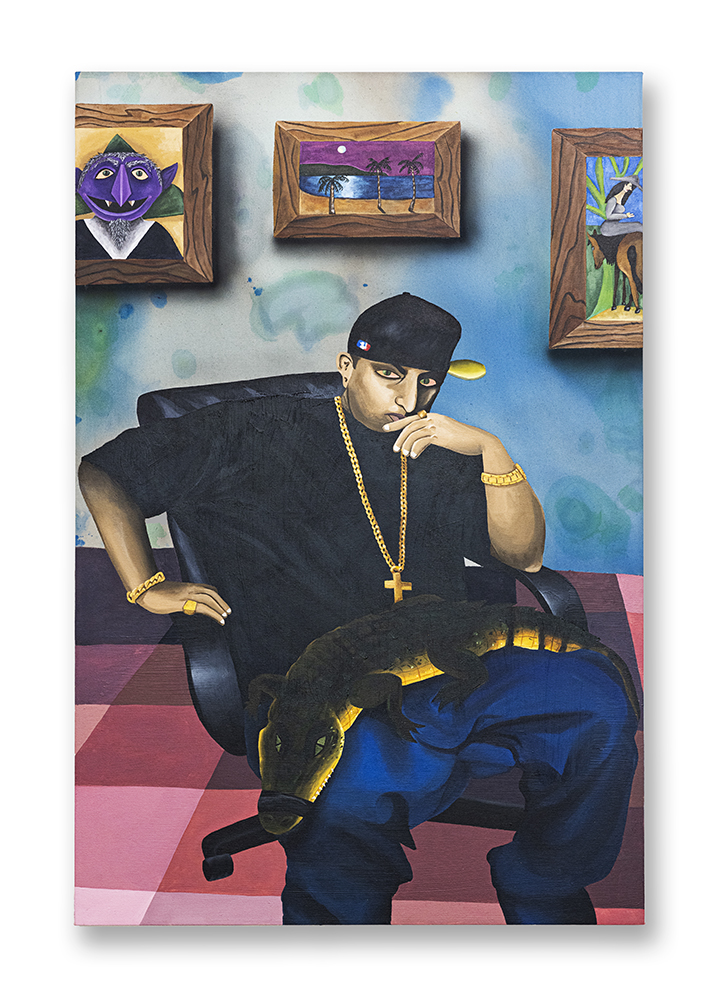

Ñengo Flow y su caimán

2023 Acrylic on canvas 60 x 40 in

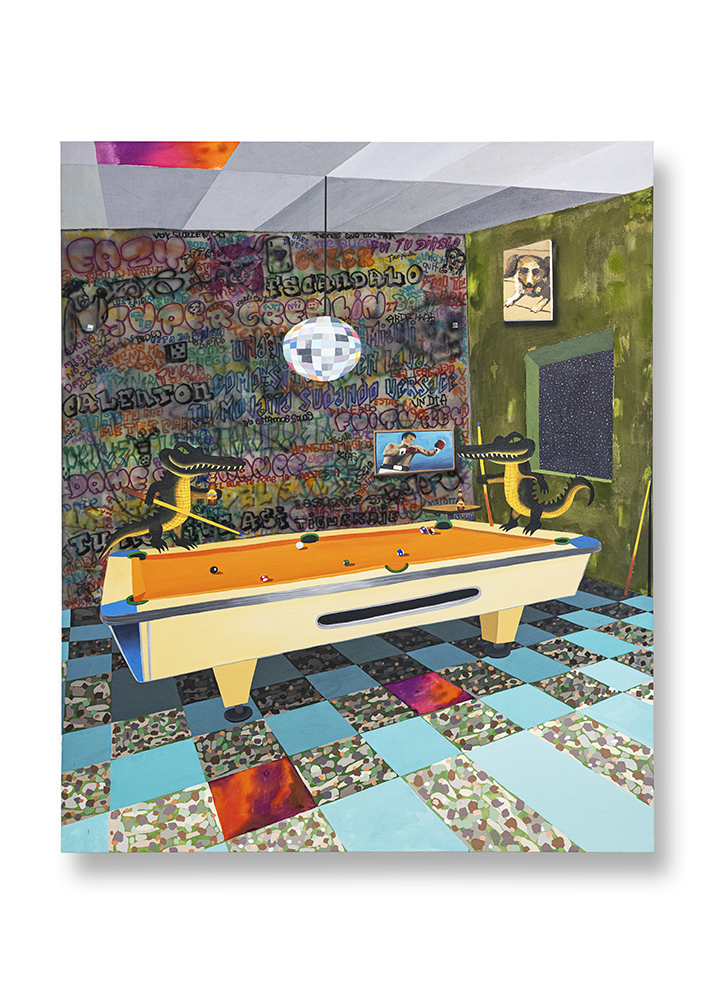

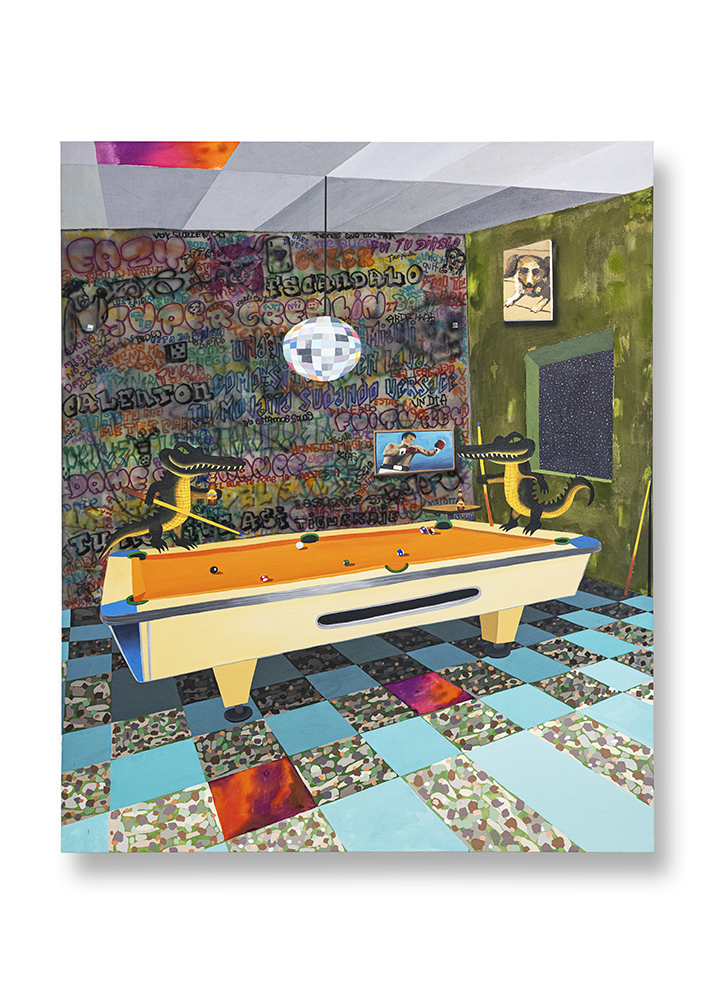

La Guarida del Caimán #1 (Vega Baja)

2023 Acrylic on canvas 67 x 53 in

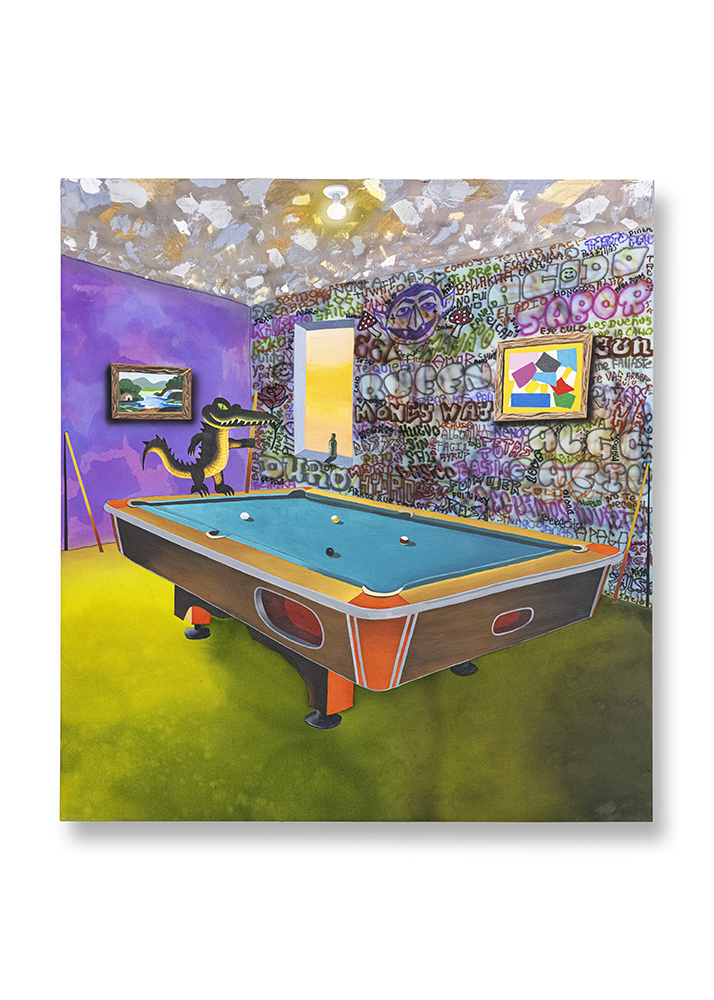

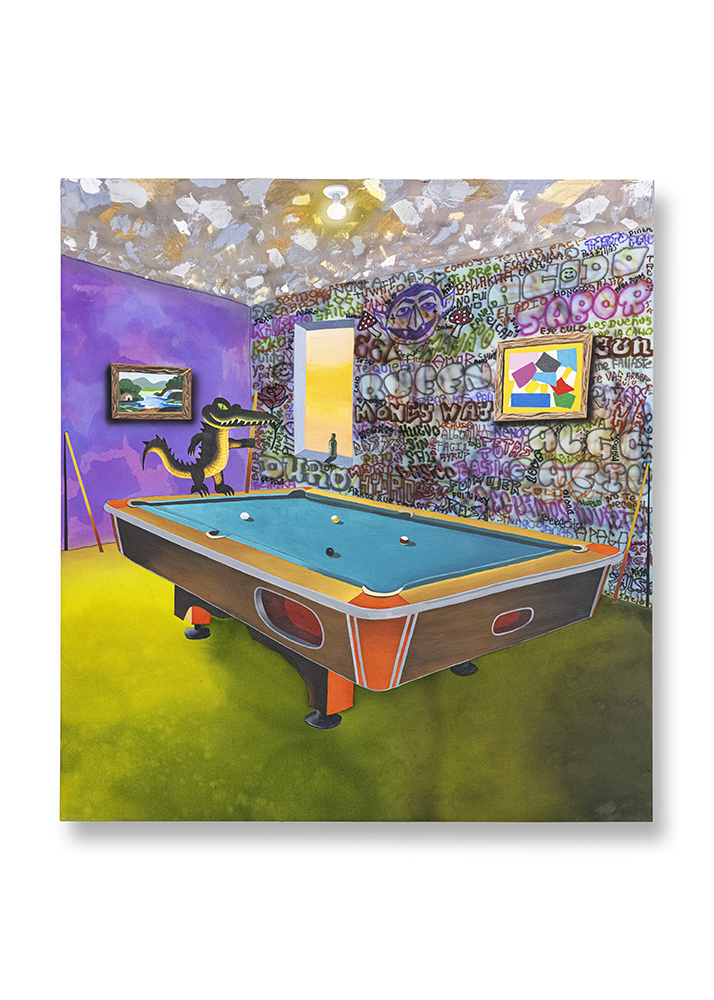

La Guarida del Caimán #2 (Vega Baja)

2023 Acrylic on canvas 72 x 60 in

La Guarida del Caimán #3 (Orocovis)

2023 Acrylic on canvas 50 x 46 in

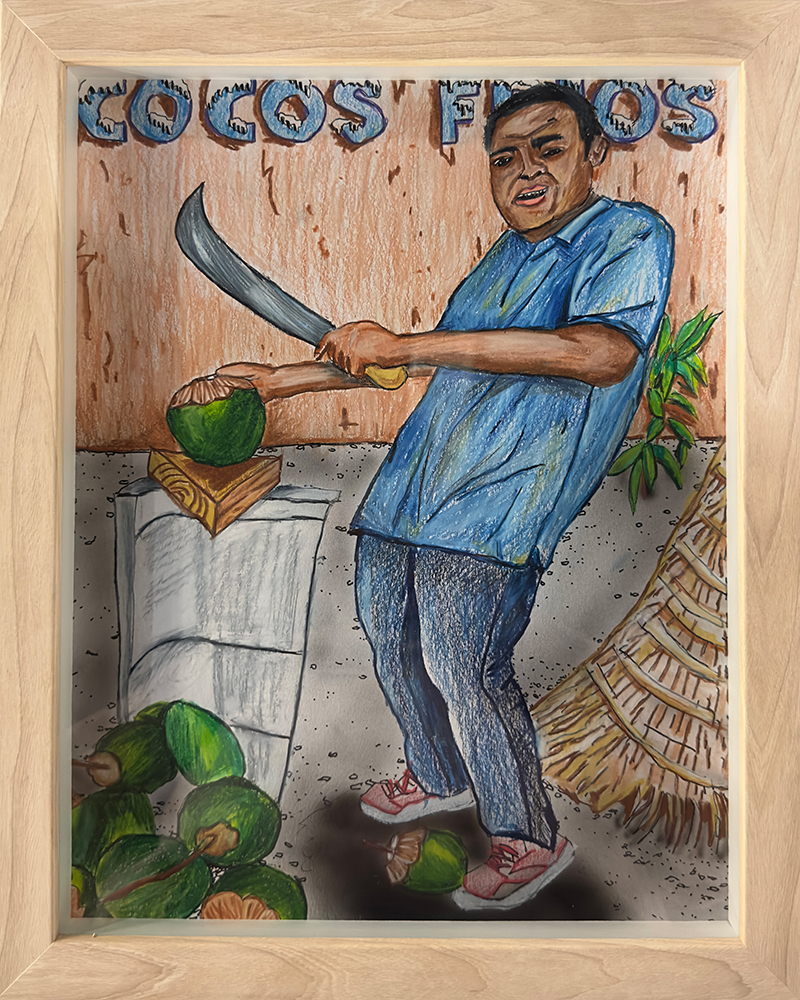

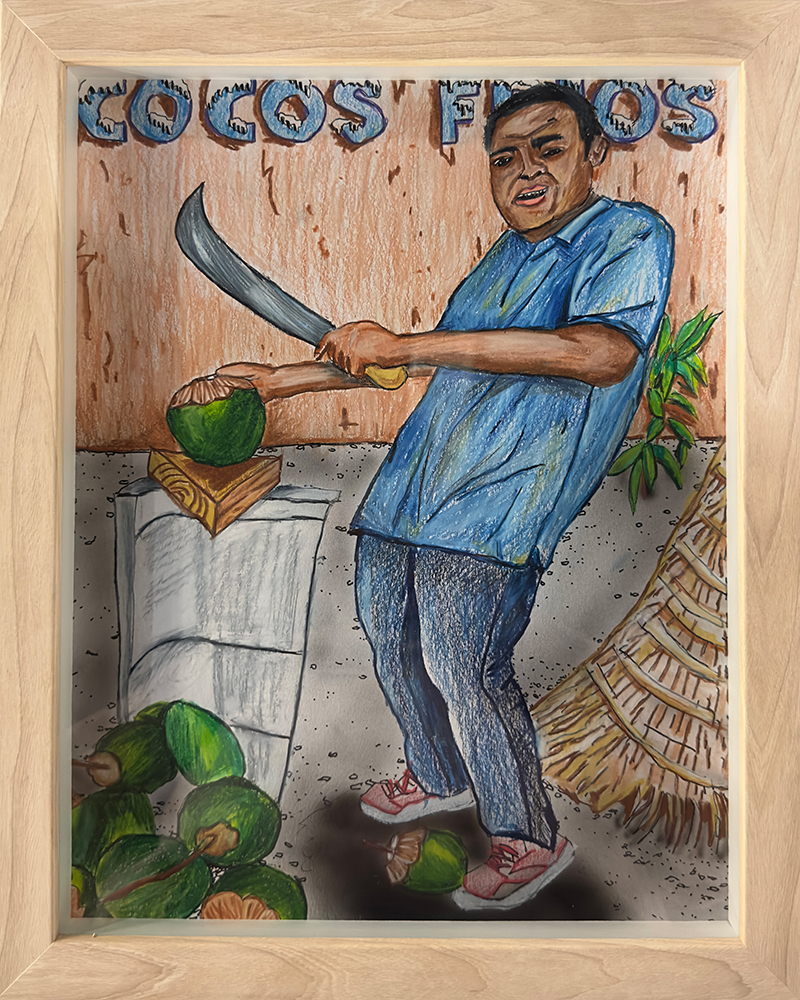

Cocotero de San Juan 721

2023 Colored pencil on paper 15.59 x 12.60 x 1.38 in

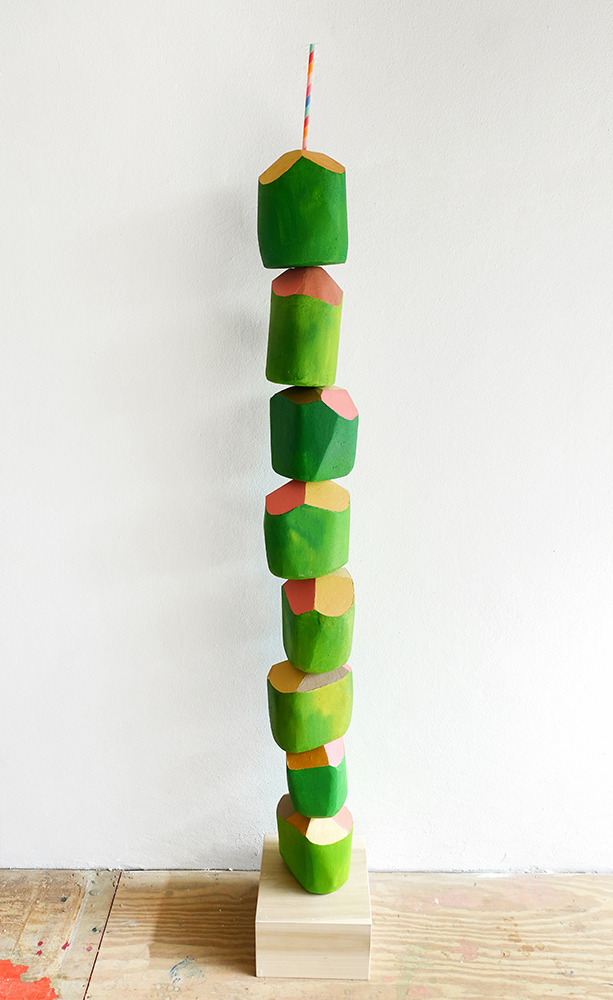

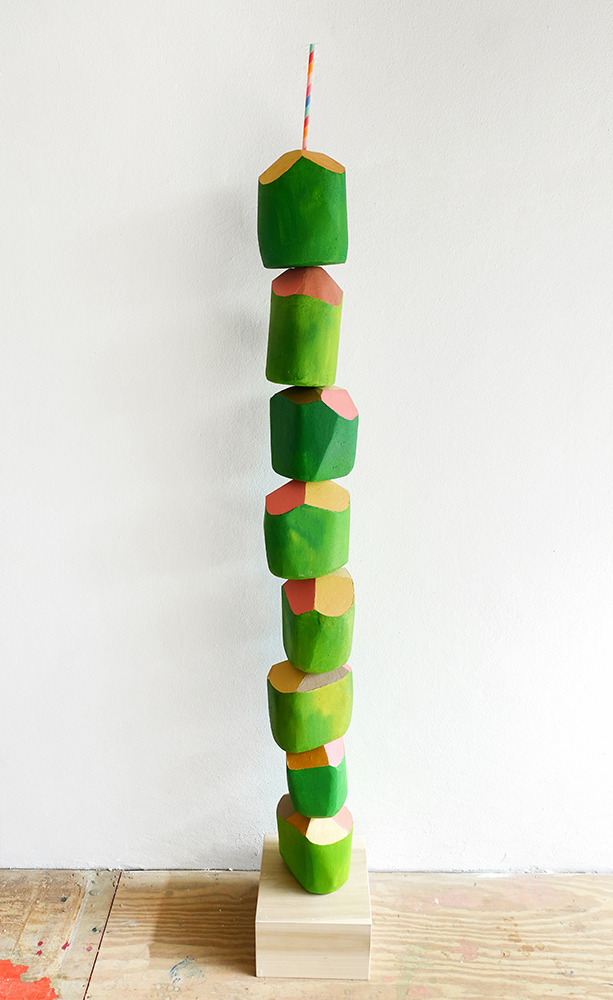

Endless (Coconut) Column, version 3

2023 Acrylic on polyurethane foam on poplar wood 82 x 11.4 x 11.4 in

Endless (Coconut) Column, version 2

2023 Acrylic on polyurethane foam on poplar wood 58.6 x 11.4 x 11.4 in

Endless (Coconut) Column, version 1

2023 Acrylic on polyurethane foam on poplar wood 40.9 x 11.4 x 11.4 in

Invasive Species

2023 Installation view Art Basel Miami

Invasive Species

2023 Installation view Art Basel Miami

Invasive Species

2023 Installation view Art Basel Miami

Invasive Species

2023 Installation view Art Basel Miami

Invasive Species

2023 Installation view Art Basel Miami

Invasive Species

2023 Installation view Art Basel Miami

Invasive Species

2023 Installation view Art Basel Miami

Don Cheo, Ojos de Caimán

2023 Acrylic on canvas 60 x 40 in

Looking for the Watermelon (Playa Los Bohios, Maunabo)

2023 Acrylic on canvas 60 x 48 in

Psychedelic Afternoon Under a Palm (Playa Los Bohios, Maunabo)

2023 Acrylic on canvas 60 x 48 in

Night Fishing in Canovanas

2023 Acrylic on canvas 53 x 84 in

Ñengo Flow y su caimán

2023 Acrylic on canvas 60 x 40 in

La Guarida del Caimán #1 (Vega Baja)

2023 Acrylic on canvas 67 x 53 in

La Guarida del Caimán #2 (Vega Baja)

2023 Acrylic on canvas 72 x 60 in

La Guarida del Caimán #3 (Orocovis)

2023 Acrylic on canvas 50 x 46 in

Cocotero de San Juan 721

2023 Colored pencil on paper 15.59 x 12.60 x 1.38 in

Endless (Coconut) Column, version 3

2023 Acrylic on polyurethane foam on poplar wood 82 x 11.4 x 11.4 in

Endless (Coconut) Column, version 2

2023 Acrylic on polyurethane foam on poplar wood 58.6 x 11.4 x 11.4 in

Endless (Coconut) Column, version 1

2023 Acrylic on polyurethane foam on poplar wood 40.9 x 11.4 x 11.4 in

Radamés ‘Juni’ Figueroa: Invasive Species

‘Invasive species’ sounds almost like military terminology. As with enemy armies, they wreak havoc on foreign habitats, disrupting whatever equilibrium has been allowed to take root. They have strength in numbers, resist local defenses, and quickly reshape their new land. Native species are forced to adapt in order to survive, generating an impossible and infinite tension that has long been at the heart of Radamés ‘Juni’ Figueroa’s practice.

Figueroa’s paintings cannot be separated from his installations and sculptures, which often incorporate happenings, music, and public participation. His works are actual habitats– living environments where perspectives and sensations are in constant shift. He disarms the viewer with his own brand of realism– not quite naive, not quite classical. Using humor and wide-ranging cultural references, Figueroa’s playful images and spaces obfuscate a complex landscape of personal and political anxieties that resists one-dimensional readings. Doubt and instability are intrinsic to the sensorial pleasures so heavily associated with the tropics.

The artist’s native Puerto Rico is the defining subject and setting for the Caimanes series. Begun in 2021, the Caiman Paintings are difficult to categorize in one genre. Intertwining portraiture, landscape, and narrative, they are, in a sense, history paintings. Caimans are non-native alligatoroids introduced to Puerto Rico around the 1960s, initially sold as pets in American department stores. Inevitably, many were illegally released into predator- less Puerto Rican rivers, where females lay up to 40 eggs at a time. Absence of dedicated government resources propelled locals to take whatever action they could, and so the island’s caiman black market was born.

Today, there are several families across the island who have specialized in caiman hunting for generations. You can buy caiman empanadas if you know where to look. Keeping caimans as pets is a status symbol in some underground cultures and narcotrafficking networks. In developing this series, Figueroa spent time with hunter families in isolated riverside communities where economic activity is continuously scarce. This makes the caiman trade essential not just to daily survival, but to the dignity that comes with self-reliance. Figueroa reflects on this uneasy symbiosis throughout the series, particularly in his portrait Don Cheo, with Caiman Eyes.

The caimans play a variety of roles across the paintings, from insouciant background actors to hunting trophies and humanoid pool players. Do they stand out aberrantly, or is there a new kind of uncomfortable harmony taking shape? Processes of invasion and colonization are never straightforward in their toxicity. The invaded culture dies and survives every day. Uninterested in direct political parallels, Figueroa’s work mines questions of hegemony, agency, and victimization.

Complicating the historic narratives at play, Figueroa’s paintings are a battleground of art historical references amidst sardonically kitsch Puerto Rican imagery. Palm trees, sunbathers, and reggaetón artists exist in imaginary rooms and beaches alongside a world-class collection of masterpieces. Ñengo Flow poses with his pet caiman in front of his Peter Doig. An Erika Verzutti watermelon sculpture is hanging out on the beach with a nude sunbather whose haircut looks suspiciously reminiscent of a Fernand Léger.

In the three paintings titled La guarida del caimán, we are in a graffiti- strewn seaside billiards bar where the caimans, posing cheekily with their cue sticks, nearly distract from the casual Matisses on the walls. A portrait of a dog is, in fact, a close-up crop of Francisco Oller’s El velorio (1893)— easily the most important painting in Puerto Rican history, with a rich and complicated legacy of post-colonial criticism. Like with the caimans, are these artworks agents of equilibrium or dissonance? Are they hierarchical signifiers of value, or a physical embodiment of universal humanity, always belonging everywhere?

Figueroa makes the self-aware high-low reversal literal with Night Fishing in Canóvanas, a tongue-in-cheek reference to Picasso’s Night Fishing at Antibes (1939). Instead of the south of France, we are transported to the Río Grande de Loíza in northern Puerto Rico, one of the island’s major waterways now teeming with caimans in many areas. The dark, swampy water contrasts with the iridescent starry sky, with a satellite that places us firmly in the island’s tech-dominated present. There is a mermaid moonbathing in the background, while the foreground features the Díaz Rosario brothers on their boat, near a caiman relaxing on a plastic alligator float. Figueroa’s work often takes symbols of relaxation and tourism and appropriates them from a Puerto Rican perspective, weaponizing humor to investigate who truly gets to relax in the tropics.

Puerto Rico is a small Caribbean island-colony forcefully made reliant on foreign tourism and capital, to the detriment of local innovation and development. Nearly every aspect of daily life is tinged with politics and the endless debate over the island’s relationship to the United States. The government incentivizes hotel development over safeguarding vulnerable natural resources, and local culture is constantly made to perform itself. In this context, the vibrant beauty of Figueroa’s subjects and landscapes belies his deep ambivalence about the practice of pleasure, leisure, and artistry itself as inherently political acts. Exuberant aesthetics couche an undertone of refusal and rebellion, paradoxically celebrating artistic subjectivity as a strategy of resistance.

Laura González

-

Art Basel Miami Beach 2022

Miami Beach

-

Frieze London 2022

London

-

Armory 2022

New York

-

Art Basel 2022

Basel

2022

-

Art Basel Miami 2021

Miami

-

Artissima 2021

Turin

-

Artissima XYZ 2021

Turin

-

Frieze London 2021

London

2021

-

Liste Art Fair Basel 2021

Basel

-

The Armory Show 2021

Online

-

Art-o-rama 2021

Marseille

-

NADA x Foreland 2021

New York

-

NADA Miami 2020

Miami

-

Artissima XYZ 2020

Online

-

Liste Showtime 2020

Online

-

Frieze London 2020

Online

2020

-

NADA MIAMI 2019

Miami, USA

-

MECA 2019

San Juan, Puerto Rico

-

ART DÜSSELDORF 2019

Naufus Ramírez-Figueroa

Düsseldorf, Germany

-

Frieze London 2019

Hellen Ascoli

London, UK

2019

-

Chicago Invitational 2019

Elisabeth Wild

Chicago, USA

-

LISTE 2019

Basel, Switzerland

-

Frieze NY 2019

Naufus Ramírez-Figueroa

New York, USA

-

ArteBA 2019

Naufus Ramírez-Figueroa

Buenos Aires, Argentina

-

NADA Miami 2018

Miami, USA

-

Frieze London 2018

Johanna Unzueta

London UK

-

LISTE 2018

Akira Ikezoe

Basel, Switzerland

-

ArteBA 2018

Elisabeth Wild

Buenos Aires, Argentina

2018

-

NADA Miami 2017

Miami, USA

-

Frieze London 2017

Regina José Galindo

London, UK

-

LISTE 2017

Naufus Ramírez-Figueroa

Basilea, Switzerland

-

Frieze NY 2017

Akira Ikezoe

New York, USA

2017

-

NADA Miami 2016

Miami, USA

-

ARTBO 2016

Akira Ikezoe

Bogotá, Colombia

-

Frieze London 2016

London, UK

-

LISTE 2016

Naufus Ramírez-Figueroa

Basel, Switzerland

2016

-

NADA NY 2016

Akira Ikezoe

New York, USA

-

SP Arte 2016

Radamés “Juni” Figueroa

Sao Paulo, Brazil

-

ARCO Madrid 2016

Madrid, Spain

-

Material Art Fair 2016

Jorge de León

México, México

-

NADA Miami 2015

Miami, USA

-

ARTBO 2015

Naufus Ramírez-Figueroa

Bogotá, Colombia

-

LISTE 2015

Basel, Switzerland

-

NADA NY 2015

Elisabeth Wild

New York, USA

2015